- Home

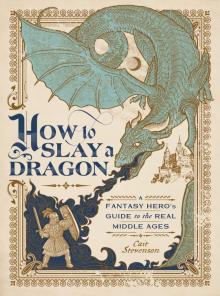

- Cait Stevenson

How to Slay a Dragon

How to Slay a Dragon Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

For Dr. Mark Smith, who knows that loving the past means passing it on

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Five years ago, someone asked me whether medieval rulers ever made plans for dealing with a dragon attacking their castle. I offered a few generic lines about the Dark Ages not actually being dark, and people knowing perfectly well that dragons are myth. But where’s the passion in that answer, where’s the imagination, where’s the history? How does it lead you into another world that’s also our own? Instead, I should have woven answers about how people dealt with fires racing from rooftop to rooftop in the Cairo slums, or imagined Londoners trying to fight air pollution. I’ve spent the past five years regretting my response that day. How to Slay a Dragon is my work of penance.

In my subtitle, I call the period that we’re discussing the “Real Middle Ages”; this is a history book, although just a wee bit nontraditional. The stories, facts, and what they say about the Middle Ages all come from peer-reviewed secondary scholarship or my own consultation of primary sources. There are very few footnotes. (On the plus side, there are also no endnotes, because endnotes were clearly invented by elf-demons with a grudge.) I’ve kept a running list of references to keep me honest. Many of the primary source quotations are mine, but lack of access to some original-language texts and my inability to read Arabic mean I’ve occasionally relied upon the efforts of other scholars. Their work is credited in a section at the end of the book.

In several chapters, my interpretation of some primary sources differs from that of current scholarship. I’ve tried to briefly justify my views in each case, but we can all be grateful that this book isn’t the place for full-blown academic arguments.

I’ve been a contributor to AskHistorians, one of the world’s largest and most successful public history forums (www.askhistorians.com), for five years (what a coincidence). Very rarely, I’ve borrowed ideas or even a few sentences from one of my earlier answers (writing as /u/sunagainstgold) in this book. Per Reddit’s terms of service, I hold the copyright to all my AskHistorians writing.

In some cases, I’ve relied upon scholarship conventions, such as the use of modern names for prominent figures (Charlemagne instead of Karolus Magnus) but the original forms for lesser-known ones (Katharina Tucher instead of Catherine). Non-Latin alphabets are transliterated (changed into our alphabet) without diacritical marks (for example, a instead of a¯). Because medieval languages love you and want you to be happy, the name of one Slovak bandit family can be written as Glowaty or Hlavaty—they’re still the same people who took the same town hostage. In cases like these, I’ve kept to one spelling throughout.

In other entries, I’ve trampled over scholarly conventions in ways that will leave other medievalists curled up in agony. Most notably, this includes the use of modern place names unless absolutely necessary. (Also, the Middle Ages ended in the 1520s, and I am unassailably correct about this. Unassailably.)

All of this is to say that the Middle Ages are the best ages, and I’ve done my best to pass on my love to you.

CAPITULUM INFODUMPIUM

A thousand years and a hemisphere. The medieval world had a thousand years and half the planet’s worth of other people you could have been.

You could have been Margaretha Beutler. After her wealthy husband’s untimely death, Beutler donated all her money to the poor and journeyed around southwest Germany for five years, funded by those who donated money to her instead of to the poor. During her travels, she was probably preaching—in an age when Christian women were not allowed to preach or teach religion in public. Until, that is, she was arrested in Marburg for being “an evil thief” and sentenced to death by drowning. Understandably, Beutler preferred to make some powerful friends who found her a spot in a monastery instead, after which she went on to lead several monasteries of her own.

Or you could have been Pietro Rombulo, the Arab-Italian merchant who moved to Ethiopia, started a family, became the king’s ambassador to Italy (and possibly India), and befriended an Ethiopian-Italian servant and a bishop.

You could at least have been Buzurg Ibn Shahriyar, who was not a real person but was still a celebrity, known for writing a book that included all the incredible stories people told him about pirates and sea monsters and islands beyond the edge of the world.

Nope.

You’re just… you. You get to live in this village fourteen miles from the nearest market “town” and 1,400 miles from a town that doesn’t need air quotes to merit the name. Everyone in your village gossips in terror-laced excitement about the apocalypse, but you just think bitterly that the apocalypse wouldn’t even acknowledge the existence of your village.

So when a mysterious stranger rides into town just before sundown, covered in dust because only the main roads are paved, shouting and waving a codex, you’re finally excited. Even better, that stranger is looking for you. (Of course they’re looking for you. You’re the hero of the tale.)

They grab a flickering torch in one hand and your arm in the other and start to drag you down your village’s only street. You’re scared, but you heroically rise to the challenge and go along.

Of course, you have to walk pretty far to find a private spot, since peasants in your region live in village hubs surrounded by farmland. Finally, the stranger spots some mud and spreads their cloak happily over it. As you both settle in, they hold the book out to you.

“Oh, I won’t be able to understand this,” you say.

The stranger shrugs. “That’s all right. Not everyone is Benjamin of Tudela, the Jewish explorer who traveled from Spain to Arabia and told tales of street warfare in Italy. But this is still a book to guide heroes who are setting off to slay a dragon, steal the throne, and defeat a few hordes of supernaturally evil creatures along the way. It’ll help to have some background about the outside world first, even if medieval peasants like you know far more about the wider world than the lack of a public education system would suggest.” They pause. “Luckily, spelling isn’t standardized yet, so at least there’s no need for a pronunciation guide.”

Incipit capitulum infodumpium

THE PLACES YOU’VE ALWAYS WISHED TO GO

The medieval world was four things: round, big, incomplete, and a sea monster.

As to the first: yes, and people knew it.

As to the other three…

In terms both geographic and painfully metaphorical, the “medieval world” was a hydra swimming in the Mediterranean Sea, its arms curling around the three continents: Asia, Europe, and Africa.

As far as you (and medieval geographers) are concerned, “Asia, Africa, and Europe” mean the northern coast of Africa as it curves around the eastern side to the south; the Arabian Peninsula and the lands to its north; western Russia north to Scandinavia; and then west across Europe to England at the farthest corner of the map. Iceland lay even farther out, beyond which was only the fearsome outer ocean. And also, cannibals.

In the reality denied by so many maps, the thinnest arms of the hydra reached even farther. They clung to the nexus (Latin unfairly fails to make the plural “nexi”) of travel networks surrounding the West African kingdoms, the Swahili city-states, India, and China. Thule traders from northern Canada trekked to Greenland and traded clayware; Norse Ice

landers sailed to the southern Canadian coast and brought home butternut squash. In short, the medieval world was a big place.

As a proper hero of a proper high-fantasy quest, your journey will take you to the outer ocean or even to southern lands so hot that the sun sets the ground on fire. Nevertheless, the thriving cultures beyond the Africa, Asia, and Europe you already know aren’t part of the “medieval world” in the same way—their cultural and political shifts can’t be forced into the same divisions of Antiquity and the Middle Ages.

As with every historical era, the Middle Ages have no definitive beginning or end, just sets of possible dates whose uniting characteristic is angering everyone who prefers different dates. Because you’re a hero and you don’t play by the rules, the dates that guide your thinking aren’t the traditional ones, which are a starting date of 476, when the city of Rome was sacked by barbarians yet again, and an ending date of 1453, when England and France finally got tired of fighting each other. Instead, you’re inclined to note that an invasion of one city does not precipitate the fall of an empire. After all, defining the end of an era based on the politics of the farthest corner of the world changes nothing for the lives of individual people.

For you, the Middle Ages are bounded by two revolutionary events that remade the map of the world in seemingly impossible ways. In the mid-seventh century, the birth of a new religion in Arabia and the zeal of its early believers drove the Arab conquest of the Near East and North Africa into southern Iberia. In the 1520s, the accidental birth of a new version of Christianity in western Europe shattered the world’s greatest and most enduring power (that would be the power formerly known as the Church).

The medieval millennium did witness two attempts to remake parts of the geopolitical map. In a successful but rather unimpressive endeavor, the Christian kingdoms of northern Iberia spent nearly five hundred years attempting to become the sole rulers of the whole peninsula. The kingdoms claimed it was an act of re-conquest, despite the facts that, first, the Christians who’d ruled southern Iberia until 711 were, in their eyes, heretics, and second, the Christian kingdoms spent most of their time fighting one another.

In the… less successful attempt to redraw the world, assorted Christian kingdoms of western Europe attempted to conquer a swath of the Near East. The First Crusade (1095–99), as it became known, worked more or less as intended. Then Muslims spent the next 150 years or so kicking the western Christians right back out. The Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Crusades failed both to repeat the success of the First and to convince western Europe of the irony of their battle cry, Deus vult (“God wills it”). It’s a little hard to label a Crusade successful when the entire crusader army is taken prisoner and when it requires one-third of France’s annual revenue to ransom the king alone. Harder still to ignore a Crusade in which the same king led his army as far as Tunisia and promptly died of horrific diarrhea.

(Eastern Orthodox Christians, meanwhile, did have some temporary success recapturing their old territory, but does anyone ever think of them? Not really. Does this book do any better with that? Also not really.)

The story of the Middle Ages that you now look to for guidance is also the story of people trying to remake the “Christian world” and “dar al-Islam” from the inside. Some would point out that, over the course of the Middle Ages, these changes included massive population growth; the rebirth and rise of cities; technological development; in western Europe, the Church’s ascension to a pretty spectacular amount of power; the rise of persecution based on religion and race; and other tidbits for trivia night. And as for politics… over the course of the Middle Ages, there were, in chronological and occasionally overlapping order:

the Burgundians

the Kingdom of the Burgundians

the Kingdom of Burgundy

the Kingdom of Upper Burgundy and the Kingdom of Lower Burgundy

the Kingdom of Arles, composed of the reunited Upper Burgundy and Lower Burgundy

the Duchy of Burgundy

the County of Burgundy

And that’s to say nothing of the part when the Kingdom of Lower Burgundy was also the Kingdom of Provence, except Provence was ruled by a count (who was also a king, just of Italy).

tl;dr: The “Medieval World”

is very big, but doesn’t truly encompass the entire globe or all the people in it;

is mostly Christian kingdoms north of the Mediterranean;

is mostly Muslim kingdoms in North Africa and the Near East;

has the also-Christian Byzantine Empire squished between Islamic and western Christian territory in Anatolia, but most people don’t care;

more or less ended in the 1520s; and

when Christians and Muslims went to war, the only thing “Deus” actually “vults” was for the French king to die of dysentery.

The People You Can’t Wait to Meet

Medieval people were, first and foremost, people. They curled up with their dogs at night in thirteenth-century Egypt, and they drew up lists of good dog names in fourteenth-century England. They cheated; they lied; they loved their kids; they knowingly gave their lives to nurse and comfort plague victims.

They were also people who followed different religions or different forms of the same religion. In general, medieval religion was less focused on lists of beliefs, and served more as the ether of the medieval world—a sort of invisible communications network that everyone knew existed, that people participated in to different extents, and that formed the backdrop or even the means to everyday actions that weren’t about it.

In the medieval world, religion was perhaps the most important factor (besides gender) in determining a person’s identity. Because, dear hero, whether you’re Christian, Muslim, or Jewish, you’ve been raised with very wrong and largely insulting ideas of what those other people believe. (Even when they’re your neighbors.) If you’re Christian or Muslim, you’ll need to know that Jews believe in a single God who is the creator of the universe. Judaism holds that Jews are God’s chosen people, the nation of Israel; and they take the terms “people” and “nation” very seriously. There are no attempts to convert others to Judaism. It’s a religion and a people united by ethnicity as much as by a shared, extensive set of religious laws. As a result, medieval Jews independently control no territory. They’re splintered into different cities across Europe and the Near East. Europe spent the second half of the Middle Ages becoming increasingly obsessed with order—be it scientific, social, or political—and defined order by punishing disorder. For Jews in the Christian west, it meant forced conversion to Christianity, expulsion from their home city or country, or pogroms that could wipe out a city’s entire Jewish population.

Which brings us to the religion that claimed for its own the Jews’ God, claimed the Jews’ Bible—even writing a sequel—and then promptly forgot the “Jews are God’s chosen people” promise. Christianity as a medieval (and modern, for that matter) religion is unique in two ways. If you’re Christian, you believe that the one God is simultaneously three: God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit. God the Son became human as a Jewish Palestinian carpenter named Jesus, who was indeed a real person, founded a religious movement (you can guess which one), and allowed himself to be crucified in order to give humans a chance not to spend eternity in hell.

Christianity’s second unique feature was a strong central power and hierarchy of officials: the Church. Yes, the Church, even though there were already multiple Churches well before the Middle Ages. The Church in the west, based in Rome, was a political power in its own right, and many of its officials were essentially lords. (Others, especially the priests who operated on the local level—like the one who visits your village—often had to work second jobs in order to eat.)

The centerpiece of medieval Christian religious life was its formal church service, called Mass, and the central ritual of the Mass was called the Eucharist. The Eucharist, you’ll want to know, is a ritual

meal consisting of wine and a thin wafer (in the west) or actual bread (in other Churches). The idea is to re-create the death of Christ (as Jesus was known almost exclusively through most of the Middle Ages) on the cross and to participate physically in the defeat of sin and death.

The third great religion of the Middle Ages, Islam, returned Christianity’s favor to the Jews by claiming the Jews’ and the Christians’ God, demoting Jesus to an important prophet, and holding to a set of sacred scriptures that adapted some of the earlier stories and added plenty of new material. If you’re Jewish or Christian, you’ll want to know that Muslims believe God—Allah in Arabic—dictated their scripture, the Qur’an, to Muhammad (also a real person, who died in 632 CE), who founded Islam and remains its central Prophet or Messenger.

Medieval Muslims’ day-to-day religious life revolved around praying, which they were encouraged to do five times a day and with a special emphasis on Friday. Wealthier Muslims, including women (who controlled their own money and property), often took their religious requirement of donating to charity very seriously. If you’re Muslim, you’ll dream of making the most important pilgrimage of them all, called the hajj. On the one hand, it was perfectly legitimate for people who couldn’t afford the trip to Mecca to never make their hajj. On the other, you had people like mansa (king) Musa of Mali, who distributed so much gold to charity on his way through Egypt that he single-handedly crashed the Mediterranean economy for a decade.

Judaism, Islam, and Christianity were not the only religions in the medieval world. Berbers and the Sámi peoples in particular maintained their indigenous belief systems. Muslim writers often interpreted Hinduism and Zoroastrianism in terms of ancient Greek mythology. And Christians… well, Christians converted pagan kings and kingdoms to Christianity, then wrote down all surviving information about pagan religion, spun through the writers’ propaganda machine.

How to Slay a Dragon

How to Slay a Dragon