- Home

- Cait Stevenson

How to Slay a Dragon Page 3

How to Slay a Dragon Read online

Page 3

In other words, saints can show you how to obey God’s commands, survive a battle, win a battle, heal the sick and suffering, help your dead relatives go to heaven, and ensure you go to heaven (but not quite yet). And, of course, they can show you how to rain death and destruction upon your enemies. All you have to do is pick a saint or two and follow their example of how to lead a pious life.

Straightforward and exciting enough for a hero, right? Just take, for example, Katherine of Alexandria. (Never mind that she wasn’t a real person. Her legend made her real in the ways that mattered, just like Margaret of Antioch and Barbara of Nicomedia.) Katherine was a third-century pagan (!) princess, exceptionally smart, beautiful, and charismatic. She absorbed all the education she could get; her father was impressed enough to build an entire library for her. Upon his death, she inherited the kingdom at age fourteen. Everyone insisted that she get married so a proper man could rule. Queen Katherine laughed and insisted she was quite suited for the task herself, thank you very much. And she was.

Katherine was a scholar, teacher, and wise ruler even before converting to Christianity, so you can be confident that the skills were hers alone. You can also be sure that she’s willing to be your mentor. As queen, she taught her subjects the basics of Christianity and then led them to conversion by example. More impressive, when the still-pagan emperor of Rome visited, she stormed up to him and ordered him to stop executing Christians. He snorted and said the equivalent of “Shut up, little girl.” Queen Katherine responded with the equivalent of something even ruder, and then used her knowledge and wit to prove he was a terrible ruler.

The last part was the most spectacular. Fifty pagan scholars challenged her to a debate over religion—fifty, at the same time. Eighteen-year-old Katherine’s rhetorical brilliance and knowledge of ancient Greek philosophy (really) turned them into mewling balls of shame.

(Another highlight? Katherine is arrested and tortured horribly for being Christian, but the torture device explodes and kills four thousand other people. Of course, the emperor had to have Katherine killed straightforwardly after that; she wouldn’t be a virgin martyr if he hadn’t. And then she wouldn’t be a saint, and you wouldn’t have her to guide you.)

The life of Katherine is a great story with a great heroine, and medieval Christians loved it. Fifteenth-century Nuremberg writer Katharina Tucher named her daughter Katrei, chose the monastery of St. Katherine as her retirement home, and eagerly read the biography of her fellow namesake Catherine of Siena (a real person). Heck, 50 percent of the infamous King Henry VIII’s wives were named Katherine!

The thing is, most Christians besides priests and nuns and Tucher were illiterate and couldn’t read Katherine’s story for themselves, so they only heard the Church’s version of how to imitate her. Which was, essentially, don’t have sex, be happy about suffering, and don’t have sex.

Bet you weren’t expecting that to be the takeaway from a story about a teenage girl who loved to read, argue, and tell kings to go shove it.

So, in the end, maybe just scrap the idea of a saint as your mentor altogether. Because consider this: half of Henry VIII’s wives were named Katherine, but so were half of his executed wives.

CONTESTANT #2: TEACHERS

The natural, logical choice for a mentor is obviously your favorite teacher. Just do it. Embrace the cliché. After all, that’s what all the students around you are doing. (Of course, all the students are male, teenage, Christian, somewhat wealthy, and literate in Latin, but who’s counting?)

Before the creation of the first universities around 1200, advanced students would trek across multiple countries to study with a specific teacher, wherever they had set up shop. (Universities basically happened when enough students and teachers were in one place that they banded together to demand special legal rights, such as not being charged by the city if they committed crimes.) So right away, you know that your potential mentor is willing to teach you, is very good at the thing you want to learn from them, and has enough experience in the role for their reputation to have reached even your village.

The only real downside to choosing a teacher in high medieval Europe was the competition among students to gain the potential mentor’s special attention. But even then, you’ll find inspiring cases of a teacher’s students coming together to make real change in the world.

Case in point: John Scotus Eriugena (c. 815–c. 877), who started off as the top scholar in Ireland. Then he was personally invited to run the school at Aachen in western Germany—the best school in ninth-century Europe. Students flocked to study with him, and why not? (Never mind the rumors.) Eriugena was a brilliant theologian, philosopher, and translator. The perfect mentor. (So what if your friend heard from his brother, who heard from their cousin, that Eriugena had some flaws as a teacher?) Under Eriugena’s leadership, the Aachen school somehow became even bigger and better. (In a thousand years, people will be confident they were just rumors.) Its glowing reputation grew even brighter. (Rumors are absolutely no basis for ruling out the idea of teachers as mentors. None!)

And sure enough, Eriugena’s leadership and scholarship united students in a way never before seen in medieval Europe. Sometime in the late 870s, they banded together during a lecture one day and stabbed him to death. With their pens.

But they’re just rumors, right?

JUDGES’ DECISION

So, your mentor?

Good luck.

HOW to TRAIN a WIZARD

I learned necromancy in both kinds with the help of the art of these books,” wrote John of Morigny (c. 1280–after 1323). “Similarly geomancy, pyromancy, hydromancy, aeromancy, chiromancy, and geonegia, and almost all their subdivisions.” Perfect. There really were forms of magic in the Middle Ages, people did practice them, and, best of all, they learned how to do it from books.

Set aside the slight problem that you almost certainly cannot read, because peasant life doesn’t require literacy skills all that often. John’s books can be your road map, and John himself can be your guide. Even better, John was a devout Christian monk. (Don’t worry—the heroically inevitable run-in with inquisitors always occurs later in a quest.)

Best of all, John wants to be your guide. He didn’t just write spell books—which he did, and with gusto—he also wrote a semi-autobiography describing how he learned, worked, and taught magic. He’s practically begging to be your guide.

Whether you can trust him is another matter.

There are three points to consider regarding trustworthiness. First, John tells the events out of chronological order—neatly disguising how the timeline of his supposed life story makes zero sense (unless he really hates his sister). Second, this purported autobiography reads suspiciously like an advertisement for why people should use his spell books instead of the popular ones. “Suspiciously like” in the sense that he says so outright. Third, as we will see, John taught himself magic in order to cheat on his homework.

According to John, he impressed his monastic superiors so much that they selected him to go study law at the university in Orleans, so he could represent Morigny Abbey to the outside world. (And as things turned out, represent it while living in the outside world, suggesting the other monks might have had a slightly different motivation for sending John to school.)

However, John promptly ran into several problems that should not have existed. First, he got interested in a book of spells and started to have demonic visions (which was apparently not a problem) but continued to convince himself that he was doing what God wanted (which was definitely a problem). Second, he was bad at magic, and so looked for help from an Italian Jew (a problem for historical accuracy, because a “Jewish sorcerer” leading a Christian to magical perdition was an odious and omnipresent literary trope). Third, he sought help for his difficulties with one book of magic from a second book of magic. This one—probably the most famous necromancer’s manual of the Middle Ages—was called the Ars notoria, which more or less means “The Notary Ar

t” but sounds much cooler in the original Latin. Fourth, John didn’t want to attend class, so he did what any lazy student would do—namely, he taught himself to be a wizard. For real this time.

Jacob the insidious Jew from Lombardy had already pointed the way. Who needs a textbook or class when the Ars notoria promises overnight learning of any subject in the world?

So John set aside his law studies to learn the ritualistic prayers that would help him study law. Each night before bed, the monk who wanted so badly to be a wizard made a practice out of reciting one prayer laid out in the Ars notoria. He was subsequently visited by a wonderful dream from which he awoke with the knowledge that prayer had promised: necromancy, geomancy, pyromancy, hydromancy, aeromancy, chiromancy, and geonegia. Things every lawyer should know.

On seven of those nights, however, John was visited by visions he had not sought. In the first one, the shadow of a hand blocked out the moon, and then stretched out along the ground toward John. But the shadow evaporated as soon as the dreaming monk cried out for help. In the second, third, fourth, and subsequent visions, some sort of demonic or diabolical creature came closer and closer to pouncing on John, ensnaring him, and then suffocating him to death.

And herein lies one of John’s key pieces of advice for wizards-in-training: If you pray for magical knowledge and the devil delivers it to you, it is definitely because your sorcery is so pleasing to God that the devil wants to interfere. Definitely.

You’ll finally know it’s time to stop for real after that vision in which an angel beats you up while Jesus gives you a disapproving glare.

And so, as John writes, his adventures with the Ars notoria came to a close. He was firmly convinced the book was diabolical and its prayers would lead him nowhere except to eternal perdition. From that point on, it was only good old-fashioned procrastination and cramming for him. (Except for the part where he retained all his knowledge of necromancy, geomancy, pyromancy, hydromancy, aeromancy, chiromancy, geonegia, and maybe law. John isn’t clear about that last part.)

Well… he brought his own adventures with the Ars notoria to a close. But did I mention the part where he trains his little sister to become a wizard?

John was a teacher at heart, you see. The whole point of his autobiography was to promote his other writing, which was primarily beginner-level textbooks. He even mentions how, at one point, he had started writing his own instruction manual for necromancy but threw it away when God convinced him it was bad.

So when his teenage sister Bridget wouldn’t stop pestering him about teaching her to learn to read (a feeling you know all too well), John lovingly gave in. And, well, the Ars notoria had granted him such quick command over the powers of fire, water, earth, air, demons, and palm reading; what better book to use to teach her how to read? No, not via the spells in the book. The actual book. That old children’s classic A is for Ars, D is for Diabolus.

Like her brother, Bridget was an eager learner and had no desire to stop with the alphabet. Unlike him, she used the Ars notoria to learn to (i) read, (ii) write, (iii) speak Latin, (iv) sing church songs, and (v) overcome stage fright. But the purity of her goals made no difference. Bridget likewise began to suffer horrific nighttime visions of the devil.

According to John, he knew instantly that the demons who drove the operation of the Ars notoria were tormenting his sister. He was equal parts terrified for her and angry at himself for leading her into a diabolical trap. John urged Bridget to swear to stop using the book of magic for any future learning, which she did. And from that day forward, she could read, write, speak Latin, sing church songs in public, and beat up demons whenever they came after her.

No, it doesn’t make sense that John would use the Ars notoria himself, realize the book was diabolical, and then tell his beloved sister to use it. The other timeline of events makes no sense, either: John used the Ars notoria, told Bridget to use it, realized the book was diabolical, kept using it himself, and then gradually realized the book was evil.

But hey, whatever tale made people read his own books, right?

His books. Which were, in fact, beginner-level textbooks. Of magic.

So much for a simple autobiography. John’s book teaches… various prayers and rituals that promise to unlock various forms of knowledge for its readers. Of course, because the title Ars notoria was already taken, John had to call his work the Book of Flowers.

His autobiographical introduction more than makes up for the less marketable title. The overarching story tells readers that the Ars notoria will corrupt them, and they shouldn’t use it. His little anecdote about trying to write a necromancy manual but throwing it away starts to make sense, too. John threw that book away because God disapproved of it. If he didn’t throw away the Book of Flowers, God clearly approved of it. In the guise of abject humility—confessing his own necromantic sins, lamenting about nearly damning his sister—John explains to the reader exactly why they should use his book to learn magic.

The medieval Church certainly saw past John’s rhetoric. In 1323, the French clergy staged a major event in which they burned copies of the Book of Flowers. This was a direct threat to John’s life. One way or another, he receded into the background after that date. Sources are silent on the rest of his life.

Oh, but the book. The Book of Flowers was copied again and again for the next hundred years. Scribes personalized the prayers in the book with their own names, or the names of the customers who had purchased the copies. People didn’t just own or read the Book of Flowers. They used it. They taught themselves its prayers, spells, and rituals. They taught themselves its magic.

John of Morigny may or may not have actually taught himself sorcery. He may or may not have actually taught sorcery to his sister. But with all the copies of the book he wrote that the Church condemned as heretical? John and Satan did, in the end, train reader after reader how to be a wizard. Readers like you.

HOW to DRESS for FIGHTING EVIL

Even the king of Sicily knew it: “Enemy powers are not repelled by pompous ornament, but rather through the necessary use of arms,” said the law.1

That’s kind of a bummer.

For one thing, it’s incorrect. Enemy forces can also be repelled by sorcery, bribery, or a cop-out deus ex machina. For another, medieval Europe liked pompous ornament. Knowing this, grouchy monk John Cassian (360–435) drew up a version of the “eight evil thoughts,” including vanity and luxuria, or reveling in excess. Under the fine leadership of the medieval Church, the eight evil thoughts became the seven deadly sins, which didn’t treat vanity as bad enough to be its own sin and limited luxury to lust.

There was still plenty of moralizing about the evils of fancy clothes and excess consumption, because it wouldn’t be the medieval Church without some moralizing. During the fifteenth century’s very literal bonfires of the vanities, priests urged their audiences to toss their makeup and fancy clothes into the flames, and some people actually did. These clothes weren’t merely inappropriate for fighting evil; they were evil.

Now, how long their zeal for God-approved austerity lasted is another matter entirely.

Despite their unattractiveness, though, Sicilian statutes from 1290 would seem to suggest the Middle Ages can offer you quite good guidance for figuring out what to wear into actual or metaphorical battle, even if specific types of clothing changed based on time, place, gender, religion, age, class, and occupation. Sometimes it’s better to cut things short and move on.

1. YES, THE MIDDLE AGES OFFER YOU GOOD GUIDANCE

Your Sicilian friends had far more to say about clothing than “don’t be a pretentious show-off,” and they weren’t alone. The 1290 code was one of very, very many so-called sumptuary laws that spread across western Europe from the thirteenth century on. Sumptuary laws could regulate consumption (no, a shared etymology does not count as a bad pun) of any number of goods. But clothing was by far their most common target. Most infamously, sumptuary laws told people what they could and coul

dn’t wear.

This did not mean half of Europe was running around without pants. Statutes were more concerned with who could wear fur, who could wear what kind of fur, who could wear how much fur, who could wear fur in specific places on their outfits and accessories, and mandating that teenage boys in Florence could not wear pink leggings and men in Nuremberg could not wear short jackets. (This last one was the city’s prim euphemism for banning a certain practice in which men enhanced a certain area of their pants to make it appear larger.)

Sumptuary laws aimed to reinforce social order by restricting various fashions to certain groups, especially by class. For example, people could wear more fur the fur-ther up the social scale they were. (What? You wanted a bad pun.)

Sumptuary laws are practically begging you to go undercover as you begin planning for your quest. Maybe not the ones that differentiated between “the king and everyone else” or “the king on Sundays and the king on every other day.” But you could learn which fashions were available to the bourgeoisie or higher, or certain professions of the bourgeoisie or higher, or the nobility or higher. And because most enforcement was left in the hands of people’s friends and acquaintances, not actual government officials, there wouldn’t be very many people to identify you as someone who shouldn’t be wearing that.

A Sicilian law that grumbled about “pompous ornaments” in general is even further proof that the Middle Ages can provide great advice for how to dress. This decree was promulgated in the middle of the long-running violent period in the relationship between Aragon and Sicily. So the requirements for men’s clothing were understandably centered on what would be more useful in battle—even if it was just to keep the men in a martial mindset. For example, that cloak of yours will be colder and less swanky without a fur lining or even an inner layer of trendy-colored fabric. But it will move much more easily in a fight.

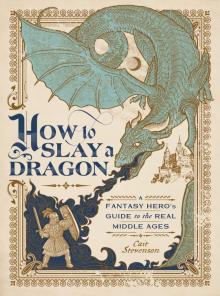

How to Slay a Dragon

How to Slay a Dragon