- Home

- Cait Stevenson

How to Slay a Dragon Page 4

How to Slay a Dragon Read online

Page 4

Under this same statute, women, on the other hand, couldn’t wear dresses with long trains. In the lawmakers’ minds, it had nothing to do with war. No, that fabric wasted on the train could have been donated to poor people.

And all of that business is to say nothing about armor.

The good news for you as a village kid is that chain mail is chain mail. There’s only so much that can be done to choose (read: purchase) the “best” metal circles and connectors. I suppose you could be the Emperor Constantine, whose mother placed shards and nails from Jesus’s cross inside his helmet and turned it into one of the symbols of his imperial status, but heroes shouldn’t depend on a literal deus ex machina for protection. So just be sure to pack a fabric surcoat to wear over the top when you’re crossing the barren wastes or anywhere else with better weather than England (so… everywhere). The sun against shiny metal will not help you stay hydrated.

The better news is that if you’re leveling up to plate armor, cities in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were in hot competition to make the best armor and get credit for it. (Who needs money when you can build civic pride? Besides everyone?)

Some cities had no hope of catching up to the leaders and didn’t even try. Someone has to make the cheap armor, after all—looking at you, London. Nuremberg and Augsburg, though, were fiercely protective of their armor and their armorers. Nuremberg didn’t even want the metal its smiths used to make armor to be sold to nonresidents, so the Germans’ strategies for keeping it all in the family are pretty much a handbook for picking out the right sword.

You can be somewhat comfortable right away knowing that masters tended to specialize in manufacturing one part of armor, like the Helmschmieds (translated roughly as “helmet-smiths”) of Augsburg being… helmet-smiths. If you ask around in a city—or beyond it, even—you can learn the names of the best armorers (like the Helmschmieds). You’ll know which master’s mark—the proprietary stamp on a piece of armor identifying who made it—to look for. Sometimes.

To make sure that the armor was functional, Nuremberg and eventually Augsburg required an inspection of finished armor to make sure every piece of metal contained a sufficient percentage of steel. Unfortunately, they never wrote down how they tested the armor, just that if it didn’t pass, it should be smashed. Hopefully not while you’re wearing it.

While “torn apart” served as a good way to identify armor that didn’t pass the tests, inspectors preferred to add a mark of their own to signify what was good quality. For Nuremberg, it was the city’s symbol of a proud eagle. In 1461, Augsburg’s guild suggested its armorers stamp on their city’s symbol: a pine cone. Yes, really. In medieval Christianity, pine cones symbolized resurrection, which is probably the one thing more useful in battle than armor.

2. NO, THE MIDDLE AGES DO NOT OFFER YOU GOOD GUIDANCE

Sumptuary laws can teach you how to dress to fight evil; armoring codes teach you how to dress to fight evil…

A brief word about using laws as historical sources.

Laws are an excellent guide to a society’s ideals, or at least a compromise thereabout. They’re a bit troublesome for figuring out what people were really doing. A statute might ban a practice because the lawmakers were worried that someone might do it even though no one was, or because everyone was doing it, or anything in between. More relevant for your purposes is the knowledge that the existence of a law does not mean it was followed.

For example, you can probably guess how strict people were about following sumptuary laws and armoring statutes.

Some Italian cities couldn’t even find people willing to enforce their sumptuary laws. Official positions overseeing their enforcement stayed vacant. Subsequent laws upped the bounty that residents received for turning in their rule-breaking neighbors. Then there were the “letter of the law but not the spirit” people, whose strategies included sneakily dying a common type of fur to look like a more prestigious kind.

At least their charade suggests how you can disguise yourself for less money.

It would be nice if armor codes did better in practice, but even here there’s a bit of hope involved. The presence of Nuremberg’s mark for quality metal in armor doesn’t relate very strongly to the composition of surviving armor, even though the city was quite shrill about people imitating its mark to pass off lousy armor as prestigious Nuremberg material. (Don’t be like Fritz Paursmid, who spent four weeks of 1502 in jail for using a master’s mark deemed too close to Nuremberg’s eagle.)

* * *

In the end, then, medieval sources do offer some guidance on figuring out how to dress for fighting evil in whatever time and place you find yourself. But sumptuary laws and armoring codes provide guidelines, not certainties. So be grateful that you have a base to work from and that you don’t have to adhere to these laws obsessively. You’ve got evil to fight—you don’t have time to let pink leggings and ermine lining, shall we say, consume you.

Okay, sometimes a shared etymology is no excuse.

1. Sarah Grace-Heller, “Angevin-Sicilian Sumptuary Laws of the 1290s: Fashion in the Thirteenth-Century Mediterranean,” Medieval Clothing and Textiles 11 (2015): 88.

AT the INN

HOW to FIND the INN

In fourteenth-century London, the smallest amount of ale you could generally buy was a quart. Not a cup, not a pint—a quart. Further, innkeepers were legally required to lock the doors of their inns at night: no one in, no one out. These policies were not at all related.

On your quest through the medieval world, you’ll need to sleep at some point, and you’ll probably want to be under something besides the stars. You might not have to stay at an inn, however. The early medieval Islamic world developed a network of combination inn/trading depots for merchants called funduqs. They had a less unsavory reputation than inns in the west. And all you’d have to do to qualify as a guest would be to possess the tangible trade goods that you can’t exactly carry if you’re fleeing a supernatural army.

For a good alternative, get religion! Churches and monasteries were required by the Church to offer overnight sanctuary to all comers (which all too often meant nobles and however much of their traveling party would fit), and religious principles of hospitality were just as deeply rooted in Judaism and Islam.

The list of possibilities of where to stay could unroll almost forever, ending with the one even your little village knew and feared—namely, the legal obligation to give quarter to any passing pilgrims or stationed soldiers. No matter how long a family had to sleep in an attic or shed.

But let’s face it: You have no problem with the crying babies you’d probably have to deal with if you demanded shelter in a private home. But you know all about quartering troops firsthand, and you don’t want to make another family nervous about an overnight stranger. The insides of churches or mosques or synagogues? Been there, done that. It’s the late Middle Ages in western Europe, and you want a nice quart of ale and a bar fight. You’re heading for an inn.

HOW YOU’LL FIND THE INN

Inns represented opportunities to make money (whether making money involved charging for rooms or something less legal), as they were places that saw a lot of travelers. In general, they’d be located in places with a lot of traffic—in towns, at pilgrimage sites, along major routes. Even better for you, they could also be found in suburbs (yes, suburbs) or on the outskirts of towns, where you wouldn’t have to pay city tolls to enter.

If you end up in a town (which you will; heroes do), you’re going to have a bit of a challenge. In 1309, London had 354 tax-paying taverns. The ones that didn’t accept overnight guests were probably balanced out by the number of one-night pop-ups just unofficial enough to escape taxes. In other words, there probably won’t be an “inn quarter” or “Tavern Street.”

As you wind through the complex of streets, you’ll be scanning buildings for the graphic signs that single out inns. In almost any city, innkeepers would hang wreaths from poles, but there were plenty o

f local variations that a traveler would have to ask about. (For example, in Paris, plenty of signs featured images of saints. Can’t fault people for wishful thinking.)

But with 354 taverns in London, there were 354 taverns competing for business. Innkeepers needed to make their establishments stand out. They usually settled on the incredibly novel strategy of coming up with names. That’s not to say they were creative names: When William Porland recorded the names of fifty taverns in the fifteenth century, six of them were called the Swan. But it wasn’t really the innkeepers’ fault. There was no reason to distinguish an inn by a written-out name when literacy rates maxed out in the 30 to 40 percent range, which meant a 60 to 70 percent chance that the clientele couldn’t read a name and the innkeepers themselves couldn’t write it. Businesses often took on the names of sign-friendly graphic symbols that would be quick to catch the eye. This often led to inns adopting heraldic symbols, because everyone would recognize their meaning. The same emblems that knights and noble families adopted to signify the pride and prestige of their lineage were identifiers of places where you could watch other people get drunk and do stupid things.

Not every inn used a heraldic charge as its sign and name. Saints’ iconography was popular, of course, meaning that you could drink at a good assortment of Katherine Wheels—you know, the gruesome device built specifically to torture St. Katherine of Alexandria.

In other words, pay some attention after you walk into the inn, too.

WHAT YOU’LL FIND AT THE INN

An inn that you stumble upon in the west (outside of the Islamic regions of Iberia) isn’t going to be one of those three-hundred-bed funduqs in Cairo or anything nice like that. But by the late 1300s, any respectable city is going to have at least one respectable inn with up to twenty small guest chambers, or fewer but larger dorms.

You, of course, will not be able to afford this.

Not that you’ll be able to tell by looking whether an inn is sufficiently disreputable to fit your budget. In towns, at least, inns tended to blend right in with the other buildings in the cityscape, maybe even being indistinguishable from the ordinary houses or shop-and-apartment buildings on either side. And why not, since inns were often based on household layout and even run as family businesses?

Whether you enter directly off the street or climb up to a second floor above a space for stabling guests’ horses, you’ll step into a common room containing one or more tables, benches, and inn guests eager to teach you new definitions of ignominious. The kitchen and maybe the latrine will attach directly to the common rooms, but hopefully not to each other.

As with apartments above regular businesses, you’ll make a deal with the innkeeper for a bed (well, part of a bed) in the sleeping quarters upstairs. Ideally, you’ll reach your (very shared) room by stairs. The alternative was by ladder, an interesting design choice considering the common room was essentially a bar.

WHO YOU’LL FIND

Sorry to kill your romantic dreams of going somewhere solo—no quest succeeds without a full traveling party, and a tavern common room offers your most fertile recruiting ground. After all, every innkeeper seeks to make their guests spend as much time as possible in full view, which is to say, spend as much money as possible on drinks and food. Taverns catering to a local clientele were sometimes patronized by men (and the occasional woman) practicing the same craft or other job. But on the road, all bets were off except the ones placed over dice and chess.

You’ll see pilgrims, messengers, petty merchants, servants, soldiers, new immigrants—anyone whose money a particular innkeeper was willing to accept. There would still be more men than women; Greek miracle stories and Italian farces show that rape was a very real threat for women staying in inns, and gaining a bad reputation was almost inevitable. It won’t surprise you to see people with all sorts of skin colors, especially the closer you get to the Mediterranean.

Taverns and inns had a staff too—possibly just the members of the family who owned it and a couple of servants. And then there were the nonstaff “workers” there to earn whatever money they could. Like the bard in the corner.

Did I mention there would be a bard?

HOW to PUT UP with the BARD

Put up with”? Why the pessimism?

It’s the Middle Ages! The age of romance, of poetry, of song! An age of music like none other! Don’t believe me? Then let’s take a look at ninth-century Samarra, near Baghdad, where rival celebrity divas cultivated fan bases who reportedly hated one another. In fifteenth-century England, the official band of York went on tour to play concerts in other cities. Twelfth-century France saw accusations of behind-the-scenes sex and other debauchery. And, of course, Palestine at the turn of the fifth century had a scholar who spent much of his life living in a cave, ranting about popular music as a gateway to worshipping demons.

Truly, an age like none other.

The chance to explore entire worlds through music will be one of the most exciting (and least deadly, for that matter) things about your quest. According to romance poet Jean Renart, at the beginning of the thirteenth century, singers performed alone or were accompanied by a type of fiddle called a vielle. You might hear trumpets, flutes, pipes, other wind or string instruments, or drums that could drown out the thunder. Or you could get really lucky with two for the price of one: the very popular pipe and tabour consisted of a flute and drum played at the same time, by the same person.

To hear all these melodies, you didn’t have to be in cities or courts. Like the York town musicians, plenty of Europe’s best instrumentalists and singers put in their fair share of travel. In 1372, for example, Prince Juan I of Aragon paid to send four of his court musicians to Flanders, where they could get up to speed on the hottest music trends. On the way home, they were directed to stop in Paris and play for the French king. Relevant detail: Juan trusted that his musicians were good enough for the other king to see their performance as a gift, instead of bad enough for the other king to start a war.

Not everyone could afford to be so trusting. Medieval Europe had its great musicians, and then its musicians who dreamed of being great. Especially at inns and on the road.

There was another way that medieval musical culture was truly like no other that ever existed: its high number of musicians with no other appreciable skills. When minstrel guilds like that in York got their cities to ban performances by nonmembers, and guilds’ primary responsibility was quality control…

Oh. That’s why the pessimism.

So yes, when the pesky and overly enthusiastic bard won’t let you stop them from joining your traveling party, you’re going to need some strategies to deal with it.

STRATEGY #1: BE DEAF

The medieval world was not generally kind to people with disabilities—it’s pretty telling that much of the evidence about their lives comes from stories of their miraculous “cures.” But that hardly means deaf people were helpless. One village in 1270s Switzerland invented a rudimentary sign language for a deaf-mute boy named Louis, who made himself into a successful blacksmith.

So why not turn your disability into an advantage when you can? Deaf Spanish nun Teresa de Cartagena (her surname, not birthplace) sure did. In medieval western Europe, the primary responsibility of nuns and monks was to sing prayers every day, for most of the day (and night). Teresa (born around 1420) used her deafness as an inspiration to write two books. In the first, Grove of the Infirm, she turned the social downsides of deafness—such as the inability to hear religious music and fully participate in prayers—into internal fruits that shut out the world to help deaf people focus on God. In her second book, Wonder at the Works of God, she politely gave people who insulted her a very, very long list of reasons they were wrong.

Oh, and Teresa is one of Spain’s earliest known women writers.

Be like Teresa. Rejoice in your ability to tune out that bard without even trying, and tease the people who can’t.

STRATEGY #2: BIDE YOUR TIME

&nb

sp; If you can only imitate Teresa’s subtle revenge on those who bullied her, just grit your teeth and wait for your bard to slip up like traveling entertainer “Monsieur Cruche” did in 1515 Paris. He wrote and apparently performed something described as simultaneously a sermon and a farce, which got him hauled before King Francis I. That the central characters of this farce were very unsubtly Francis and his mistress might have had something to do with that.

As the rumor went, at least, Francis decreed that Cruche should be stripped to his underwear and whipped. Granted, those screams might not be quite enough music to your ears to make up for all the pain the bard has caused your eardrums, but it’s a start. Francis certainly thought it wasn’t enough, because he also wanted Cruche to be tied inside a sack and thrown right out the window into the river below.

However, it seems that Cruche got out of the finale of his punishment by claiming he was a priest and only subject to ecclesiastical law, etc., etc. Apparently Francis forgot that Cruche was an actor, and the members of his court were secretly delighted enough by the farce to stay quiet.

And no, in your case, there’s no chance you’ll be lucky enough that the bard will repent their ways and find a new career. But don’t despair! Cruche’s escape highlights three very relevant points for you as you journey. First, having a member of your party who’s skilled at disguising themselves as a person with strong social standing will be helpful. Second, the standard way to claim benefit of clergy in the late Middle Ages was to show you could read Latin, a skill that will also prove useful. Third, the rumors that popularized Cruche’s story likely repeated the farce’s contents correctly and almost certainly exaggerated the potential punishment. So even if your entire party gets blamed for your bard being… a bard, you probably won’t die.

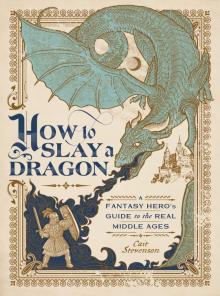

How to Slay a Dragon

How to Slay a Dragon